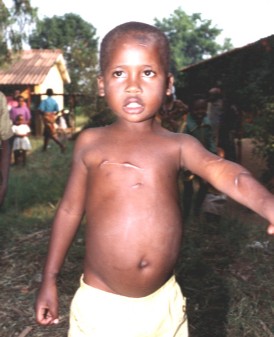

Rwanandan boy with machete scars

Countryside in Rwanda

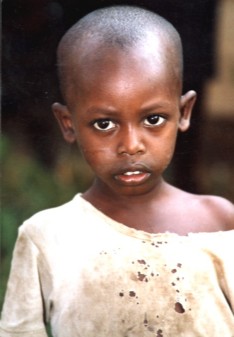

Rwandan orphan

I am a high school senior at Westmont High School in Campbell, California. As part of the graduation requirement at Westmont, each senior is required to complete a Senior Project, which consists of an extensive 10-15 page research paper, a product, and a presentation. Students are allowed to choose their own topics, anything from the history of alchemy to the significance of children's art work. I chose to investigate U.S. and international policy on the 1994 genocide in Rwanda. I was 10 years old when it happened and I heard about it. When I saw a Nightline piece on Rwanda today, eight years after, I knew that I had to know more.

When the terrorists bombed the Pentagon and the World Trade Center, the United States pulled together to raise hundreds of millions of dollars in memory of the thousands who died on September 11th. Networks pulled regularly scheduled programs to air benefits aiding the families of lost firefighters and other victims. Countries all over the world sent symbols of their support and sympathy. British Prime Minister Tony Blair, in television interviews declaring himself shoulder to shoulder with his American friends in this hour of tragedy, has traveled to Berlin, Paris, New York, Washington, Moscow, Islamabad, and Delhi on behalf of the war against terrorism. Yet, when hundred of thousands of Rwandans were slaughtered, the world reacted far differently and with considerably less empathy. Leading countries and world leaders often turn away from desperate situations which need immediate assistance, as seen through circumstances surrounding the murders in Rwanda in April 1994. The policies, actions, and words of world organizations and countries show negligence and selfishness in addressing the 1994 slaughters properly.

There are three different types of people in Rwanda—the Twa, the Tutsi, and the Hutu. Only making up around one percent of the population, the Twa role in the genocide is virtually non-existent. The farmers and cattle herders of the land were known as the Tutsi tribe. The Tutsi clan owned the large herds of cattle, while the Hutu farmed the land and the Twa gathered in the fields and forests. According to Fergal Keane in Season of Blood, the Tutsi nobility that dominated Rwanda “stressed the importance of physical stature, that is, they claimed their tallness and aquiline facial features were synonymous with superiority” (Keane12). The Hutu, shorter and stockier, “who worked the land, and who had neither the cattle nor ties to the nobility” became second-class citizens in Rwanda (Keane12). Status between Hutu and Tutsi could be changed depending on the amount of cattle a person owned.

Early European colonists only promoted the class system enforced by the Tutsis when they arrived in Rwanda. These Europeans believed the Tutsi to be a race of black Aryans, who might have migrated from Ethiopia, coming “into the dark and savage lands in the heart of Africa to impose their superior civilization” (Keane 13). Without supporting evidence backing their assumptions, the Europeans were nonetheless certain that the Tutsi were superior to the Hutu, the Hutu superior to the Twa, and they were just as certain in believing “themselves to be superior to all three (Human). The Germans, who stayed until 1917, colonized Rwanda and the neighboring country of Burundi, which shares a similar make-up in population, in 1899. Rwanda then went under Belgian rule as mandated under the League of Nations until it won its independence in 1962 (Lemarchand 12).

Racial strains were furthered in 1933 when the Belgian government instituted identity cards, which were required to be on persons at all times. This practice meant that “every Rwandese was henceforth (on the basis of quite arbitrary criteria) registered as Tutsi, Hutu or Twa” (Sellström). The Catholic Church, a dominant force in pre-colonial Rwanda, also openly favored Tutsis and discriminated against Hutus (Sellström).

In 1959, the Bahutu Manifesto, a “profession of faith in democracy” and “plea for social reform,” instigated the Hutu revolution against Tutsi rule that eventually led to the “proclamation of a de facto republican regime” (Lemarchand 14). The United Nations administered the new elections held in September of 1961, which “merely confirmed” the “de facto supremacy of the pro-Hutu party, the Parti de l’Emancipation du Peuple Hutu” (Lemarchand 14).

Northern Hutus, who had previously been able to escape Tutsi nobles before the colonization, revolted in the beginning of the 20th century but were contained by the Germans and their Tutsi allies. According to Keane, bitter memories lingered from the suppression of the revolt, helping make northern Rwanda a “hotbed of Hutu nationalism” (Keane 17). This helps to explain why those who came to dominate Rwandan politics after the first stage of independence, including President Habyarimana, came from the north (Keane 17).

In the months leading up to April 1994, there were warnings about a possibility violent uprising. One of them included a fax sent on January 11, 1994 by General Dallaire, Force Commander of the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda, to Major General Maurice Baril of the United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations and Kofi Annan, head of Peacekeeping Operations. This fax discussed an informant with inside information: The informant who essentially laid out for the United Nations force commander what was being planned in Rwanda, that an extermination was being planned of Tutsis, was a man who had first been a member of President Habyarimana's security staff (in other words, he was a top ranking military security official) and had now been hired through the president's political party (which was essentially indistinguishable from the apparatus of the state) to run an interahamwe militia training program for the city of Kigali, training Hutu combatants to kill Tutsi. And he tells in his information very clearly, that he thinks that his men could kill 1,000 Tutsis in 20 minutes. (Frontline/WGBH)

In this alarming fax, Dallaire also mentioned “a plot to assassinate Belgian UN peacekeepers and Rwandan members of parliament, and the existence of lists of Tutsis to be killed” (Ferroggiaro). According to the article “The Holocaust Without Guilt,” Kofi Annan, the current secretary general of the United Nations, was “told by a UN official in Rwanda” that weapons were being “stockpiled for the terrors to come” (Hentoff). When this official requested Annan’s permission to confiscate the weapons, he was denied. Yet, the UN treated this extraordinary information like any other routine bureaucratic matter because they can only give a certain amount of attention to a certain matter given the bulk of their workload. The reaction from the UN was grossly disproportionate to the gravity of the document and highly disrespectful towards the Rwandans.

On April 6, 1994, the plane carrying Rwandan president Juvenal Habyarimana and Burundi president Cyprien Ntaryamira crashed into the presidential palace in Kigali, Rwanda. Habyarimana’s supporters accused the Belgians of involvement in the assassination, but never found proof. Others suggested that the French assisted in the assassinating because Habyarimana was no longer useful to them. The Human Rights Watch reports that some in the dead president’s own circle might have wanted to eliminate him in order to avoid the installation of a new government that would diminish their own power.

Before an hour passed, “the Presidential Guard, elements of the Rwandan armed forces (FAR) and extremist militia (Interahamwe and Impuzamugambi) set up roadblocks and barricades and began the organized slaughter, starting in the capital Kigali” (Ferroggiaro). Men, women and children were “shot, speared, clubbed, or hacked to pieces in church compounds and courtyards” (Lemarchand 18). Early coverage of the killings “conveyed the sense that the genocide was the result of some innate inter-ethnic loathing that had erupted into irrational violence” (Keane 6).

A memorandum from the Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of Bureau of African Affairs, through the Under Secretary for Political Affairs, to the Secretary of State Warren Christopher after the assassination of President Juvenal Habyarimana is additional evidence of American’s knowledge and negligence in dealing with Rwanda (Ferroggiaro). This document warned Christopher of the president’s assassination, estimated “widespread violence” to be likely upon the death of the president, and predicted of the military’s intention to take assume control (Bushnell). Still, nothing happened.

On April 11, 1994, more evidence of outside knowledge of the massacres became apparent. This memorandum from the Undersecretary of Defense for Middle East Africa to the Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security, also warns of the inevitable disaster. It was used as a briefer before a dinner between the Frank Wisner, the Under Secretary and third highest ranked official in the Pentagon, and former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. In the document, Pentagon specialists warn that it was “highly likely that inter-tribal killings will spread” and “massive (hundreds of thousands of deaths) will ensue” (Deputy). There are also predictions that the United Nations “will likely withdraw all UN forces” and that the United States will not get involved “until peace is restored” (Deputy). Rwanda, denied proper consideration and assistance because it has no “strategic significance, no wealth, too many people, and not enough land,” is sadly of “little interest to the world powers” (Hilsum).

So the slaughter continued, while the world looked away. On April 30, 1994, 250,000 Hutus fleeing the onslaught of the Tutsi RPF, crossed the border into Tanzania (Frontline/WBGH). Hundreds of thousands of Hutu refugees in Congo were also hunted down and killed by the Rwandan Patriotic Front. Unfortunately, these murders went uninvestigated because they occurred in eastern Congo, which was occupied by Rwandan troops, and because the Congolese government, being backed by the Rwanda, was blocking any United Nations inquiries. By the end of 100 days, around 800,000 Tutsi and moderate Hutu had been slaughtered in a country that had started out with a population of 7 million citizens. Hundreds of thousands of Hutu refugees died of “battlefield casualties, cholera, dysentery, and famine” (Lemarchand 10). Experts describe the “killing spree,” carried out mostly by machete and clubs, as “five times more efficient than that of the Nazis” (Pope).

The international community failed to protect Rwanda in their hour of desperation and greatest time of need. Western nations sent soldiers into Rwanda in the first week of the genocide to evacuate their own citizens and then left immediately afterward. The United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR), established in October 1993 to keep the peace and assist the governmental transition in Rwanda, tried very little to intervene between the killers and civilians. and between the Rwandan Patriotic Front and the Rwandan army. When the killings were in “full spate,” UNAMIR soldiers remained in their barracks waiting for orders (Hilsum). Hilsum reports that UNAMIR failed not only to save Rwandan citizens, but failed in evacuating UN staff working for efforts such as UNICEF and UNHCR. UN Secretary-General Boutros-Ghali even refused to let Rwandans who were UN staff to leave. At least six were eventually murdered (Hilsum). On April 21, 1994, the United Nations Security Council, at the request of the United States, Belgium, and others countries, actually voted to remove all but a small part of UNAMIR.

The United Nations attempted to redeem themselves when they met on May 16 and finally arrived at a compromise. UNAMIR II would consist of a more robust force of 5,500 troops. Unfortunately, the world community failed to deliver, as the full complement of troops and material did not arrive in Rwanda until months after the genocide ended. *As stated by Daniel Benjamin in “The Limits of Peacekeeping”: “Few countries want their soldiers confronting civil wars and marauding gangs now laying Africa to waste.” However, the Rwanda report commissioned and published by United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan reveals the international community’s difficulty in reacting “with speed to unfolding humanitarian disasters” (Shawcross). The report believes the reason to be both organizational—“within the U.N. machinery itself—and political—within the dynamics of member states, and particularly the permanent five members of the Security Council” (Shawcross). Still, these findings are meaningless to the Rwandan refugees who saw their mothers and fathers, husbands and wives, and brothers and sisters needlessly and viciously cut down before their eyes.

The U.S. government was “rightly ridiculed” for “requiring seven weeks to negotiate the lease for armored personnel carriers” (Human). Our government can claim responsibility for a series of callous actions: It led a successful effort to remove most of the UN peacekeepers who were already in Rwanda. It aggressively worked to block the subsequent authorization of UN reinforcements. It refused to use its technology to jam radio broadcasts that were a crucial instrument in the coordination and perpetuation of the genocide. Indeed, staying out of Rwanda was an explicit U.S. policy objective. (Powers) With evidence such as the documents mentioned earlier, Rwandan genocide specialist Alison L. Des Forges suggests that U.S. officials knew “two days, not two weeks” after the initial killings that extremists “with an avowedly genocidal agenda had murdered legitimate Rwandan authorities” and were seizing power in the government (Forges). The United States, giving vague excuses about “tribal warfare” and “ancient ethnic hatreds,” refused to use the word genocide so it could disregard the “international convention on genocide, which demands that signatories intervene” (Sharlet). The New York Times quoted: "No member of the United Nations with an army strong enough to make a difference is willing to risk centuries-old history of tribal warfare and deep distrust of outside intervention" (Omaar). Western troops, “numerous, heavily armed, and prepared to kill,” never got their chance to defend the Rwandan civilians against the “barely trained amateurs” of the Hutu extremists (Kelly). Perhaps the United States thought finished its obligation to Rwanda in helping negotiate the Arusha Peace Accords in 1993. This agreement, which “pledged a cessation of hostilities, repatriation of refugees, and installation of a new broad-based transitional government,” proved its futility within a year (Feil).

Failing Rwanda was not entirely American’s fault as a country—the Clinton administration clearly showed their apathy towards Rwanda. Analysts believe that the Clinton administration feared that, with the congressional elections looming, the president’s party could “lose votes if the president admitted genocide was underway in Rwanda and he wasn’t going to do anything about it” (Hentoff). In his memoirs, Boutros Boutros-Ghali, the former United Nations Secretary General, recalls President Clinton “all but [shrugging] off Rwanda” (Meyer). Clinton preferred discussing the appointment of an inspector general at the United Nations and pushing for his candidate for the position as director of the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (Meyer).

Former president Bill Clinton eventually tried to make amends for his wrongdoings. In March of 1998, President Clinton traveled through Africa and made a quick stop in Kigali, Rwanda. To the audience that included survivors of the genocide he apologized: The international community, together with the nations in Africa, must bear its share of responsibility for this tragedy as well. We did not act quickly enough after the killing began. . . . .We did not immediately call these crimes by their rightful name: genocide. All over the world, there were people like me sitting in offices, day after day after day, who did not fully appreciate the depth and the speed with which you were engulfed by this unimaginable horror. (Rauch) Critics call this statement typical of Clinton’s style. Nowhere does he admit to guilt. Maybe the United States denies any blame because it truly does not believe a mistake was made. Even in the highly competitive presidential debate in 2000, Republican candidate George W. Bush and Democratic candidate Al Gore agreed that the U.S. made the right decision in not sending American troops to Rwanda (Benjamin).

Madeline Albright, the United States ambassador to the United Nations in 1994, was another official who failed to address the problem. She opposed leaving even the “token” force, reduced from 5,000 to 270 troops, when the Security Council voted on the size of the United Nations contingent in Rwanda (Corry). Albright was one of the many Western officials trying to “[block] attempts to strengthen the peacekeeping force” and “deny the reality of the genocide” in order to avoid a mandatory intervention as required by the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Shawcross) (Meyer).

David Rawson, the United States ambassador to Rwanda in 1994, also played a key role in the United States’ role in the Rwanda genocide. According to Rakiya Omaar and Alex de Waal of Covert Action Quarterly: Rawson . . .encouraged the extremists in derailing the peace process by echoing their claims that it was the RPF that had created all the obstacles to peace. Senior RPF members report that when they presented evidence of the planned genocide, the ambassador dismissed them with the charge that they were just looking for a pretext to restart the war. Rawson stayed in Rwanda ten days after the initial murders before returning to Washington. As another official in fear of the obligations that the 1948 convention on genocide required, he took another eleven days to declare an official state of disaster. Ambassador Rawson defended his actions with this quote: “As a responsible government, you don't just go round hollering genocide. You say that acts of genocide may have occurred and they need to be investigated” (Omaar).

Yet, the blame cannot be placed entirely on the United States. The French newspaper Le Figar reported that France provided the Hutu-led Rwandan government with arms during their slaughter of the Tutsis (Democrat). The missile that shot down President Juvenal Habyarimana’s plane was also French made (Kiley). The newspaper goes on to charge that France continued dealing with the killers after voting in favor of a United Nations arms embargo (Democrat). France, however, “absolv[ed] [itself] of any direct complicity in the massacre of as many as 1 million people” (World). A French parliamentary inquiry commission’s report on the genocide in points the finger to the United Nations and the United States. This report also concludes that the “ ‘passivity and inertia’ of the international community” was due to “U.S. timidity following its earlier peacekeeping debacle in Somalia” (World). Rwanda renounced these claims, asserting that France did indeed arm the Hutus and them escape after the killings.

As claimed in the French report, part of America’s “feeble response” to the genocide in Rwanda stems from the failure just the year before in Somalia (Moszynski). On October 3, 1993, Somalian men, women and children armed with automatic weapons and rocket-propelled grenades ambushed members of the U.S. Rangers and Delta Force, who were on an operation to capture warlord Mohammed Farah Aidid. Unfortunately, the situation went unbelievably tragic: The 'battle of Mogadishu'- a planned 90-minute mission which turned into a deadly 17 hours - is generally forgotten by most Americans. But five years later, it continues to cast a long shadow on US military thinking and decision making about humanitarian/ peacekeeping operations. Its legacy, says many experts, [is] a continuing U.S. reluctance to be drawn into other trouble spots such as Bosnia, Rwanda and Haiti during the 1990s. (Frontline/WGBH Educational Foundation) The New York Times also said that involvement in this conflict “without a defined mission or a plausible military plan risks a repetition of the debacle in Somalia” (Omaar). Thousands of Rwandans might live today if American politicians had had the nerve to overcome past disappointments to help others in need.

The international community also revealed their tightfisted, selfish tendencies and lack of compassion through their concern for their economy. The United Kingdom, for example, provided only fifty trucks. Belgium, while concerned enough to contribute troops to the force, claimed to be too poor to contribute the full battalion of 800 requested and agreed to send only half that number (Human). Troops from other countries that were less well trained and less well armed filled the remaining places, producing a force that was weaker than the it would have been with a full Belgian battalion as defense.

The article “Cowardice and Conscience—A Response” from World Policy Journal, blames the international community not only for their neglect in 1994, but also for their failure to respond to the Rwandan invasion of Zaire in 1996-1997. The author also suggests that they might have even encouraged this assault, which was disguised as a “war of ‘national liberation’” (Cowardice). The rest of the world also failed in opposing the Rwandan-Ugandan invasion of the Democratic Republic of Congo in August 1998. Lack of international censure to the 1993 Burundi massacres led Hutu extremists to expect no interference or punishment as a result of their killing rampage. General Romeo Dallaire spoke most accurately, though, when he said, “The United Nations is us—all of us. If the United Nations didn’t intervene, this means that by extension we are all responsible for the genocide” (General’s).

Even without the desperate conditions surrounding the 1994 genocide, the United Nations and United States should have been giving more aid to Rwanda. In “Preventable Genocide,” D’arcy Jenish suggests that Rwanda’s external debt of $1.5 billion should be absolved. Yet, such a step would only be the beginning to rebuilding a country with a shattered infrastructure and a virtually extinct professional class. Another article, “Rwandan Sorrow,” states that at least 11% of the population is HIV positive and malaria, cholera, and other diseases are “rampant and periodically spike to epidemic levels” (Taro Greenfield). In 1997, there were fewer than a dozen doctors and only around one hundred nurses inside Rwanda. Says Taro Greenfield, “The country that had once been a bastion of orderly if somewhat squalid agrarian capitalism was reduced to Stone Age living standards.” Rwanda is also one of the most densely populated countries in the world, with 350 inhabitants per square kilometer (Lemarchand 11). Taro Greenfield agrees with Lemarchand’s report that cites overpopulation as a sociological cause for the genocide: The resulting pressure on the land must be seen as a critical factor in the background of the 1994 killings. The shortage of cultivable land was a major source of social tension in the countryside, and the steady influx of rural migrants into the urban centers greatly intensified the competition for jobs while sharpening ethnic strife (Lemarchand 11).

Such political and humanitarian disasters can only be appropriately addressed by reaching out to the youth, educating them on how to prevent another such catastrophe. In a recent survey conducted at the University of California in Riverside, only 3% of the students surveyed could knew of the genocide in Rwanda in 1994 (Huang). The possibility that other genocides will transpire is great if the current generation does not receive the proper instruction on past examples and on future solutions.

Unfortunately, schools prefer to teach United States history and to focus on domestic problems. Even in courses such as world history, the curriculum concentrates on periods such as French Revolution, the Russian Revolution, and the Industrial Revolution, which African countries have yet to reach. High schools across the nation fail to include African history in their programs, which is reflected in students’ general ignorance about the culture and land. Even when reading novels about Africa, the writers of these novels are foreigners such as Joseph Conrad instead of Africans such as Nigerian Chinua Ashebe (Sinclair). If asked to point out Rwanda on a world map, most students would most likely shrug their shoulders in uncertainty. When learning of the genocide, Former Secretary of State Warren Christopher knew so little about Africa that he was forced to pull an atlas off his shelf to locate the Rwanda (Powers). At some point, all Americans must realize that what affects the rest of the world will eventually affect the United States: “It is true that we cannot be the world’s policeman, but a realistic sense of our limited power does not make it legitimate for us to turn our backs on the massive numbers of innocent people who were slaughtered” (Pope).

Rwandan children must be educated, too, to learn from mistakes in the past and to learn ethnic tolerance and acceptance. While ethnic hatred did not contribute wholly to the genocide, the death toll would not have been so high if Tutsi and Hutu neighbors had trusted and respected each other more. Only if they attend school and eventually college can they then hope to build Rwanda up to a country of which they can be proud.

Part of Rwanda’s healing process means bringing the killers to justice. The Security Council created the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) by resolution 955 on 8 November 1994. Located in Arusha, in the United Republic of Tanzania, the tribunal’s purpose is to “contribute to the process of national reconciliation in Rwanda and to the maintenance of peace in the region” (ICTR). Members are responsible for the prosecution of persons responsible for genocide and other serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in the Rwanda and neighboring states. Among those tried and convicted include politicians such as the prime minister and the minister of foreign affairs, military leaders such as Director of Cabinet/Ministry of Defense and the Brigadier General of FAR, and media leaders such as the director of RTLM and the chief editor of Kangura Newspaper. Those convicted are not all members of the elite however. The tribunal has and will continue to convict businessmen, church leaders, and ordinary citizens for their crimes during the slaughter of 1994. Unfortunately, Rwanda still does not receive the proper attention and support that it desperately needs: “At one stage, the tribunal had to be rescued from collapse by money from the Dutch government” (Punishing). The lack of media attention, “no international news service will follow the trials daily,” shows the lack of concern felt toward Rwanda’s past and future (Punishing).

Blame does lie on the shoulders of the international community and its leaders. Yet, individual citizens also have the duty and ability to aid the victims of the Rwandan genocide. Even if knowledge of the mass murders came only after the fact, there is still much assistance that the international community can give the Rwandans. As Thomas Garafolo says in his article “Toward Global Reconciliation,” to “commit genocide, one must first deny another’s humanity. Every time we pass a homeless man or woman on the corner without a flicker of recognition, we are guilty of the same thing.” Americans, eager at the chance to help their own fallen, need to feel the same generosity and compassion in donating funds and time to the Rwanda effort. While the American government might think involvement in other nations’ affairs “worthwhile” only “when absolutely necessary to protect American interests,” the American people will hopefully act otherwise (Kelly).

The media, should it choose to, would be a tremendous help in aiding Rwanda. Television stations broadcasted continuous footage of the World Trade Center and entire newspapers were dedicated to stories about September 11. No American was allowed to forget the tragedy for one second, for the media bombarded everyone’s senses with information. With the substantial influence radio and television and newspapers wield in directing people’s interests, the media has the power to raise awareness about the deplorable conditions that Rwandans endure. Unfortunately, most “major news organizations [visit] Rwanda and neighboring Burundi only when there [is] major violence: in for a week to cover the slaughter and then back out again” (Keane 6). Journalists seem to cover Africa only for the horrendous stories that are so important for their shock-value. While this applies for many stories in the United States and elsewhere, it is especially true for Africa. Americans should be saddened to realize their obsession for scandal and “gotcha” journalism when their minds and their interest could be guided towards more weighty issues such as the genocide in Rwanda. To journalist Lance Morrow, however, the “disproportion between the two subjects is grotesque, almost a joke” (Morrow). To compare the Lewinsky scandal and the Rwanda genocide is “not just to discuss apples and oranges, but to compare. . .apples and severed heads” (Morrow). Even receiving a fraction of the attention that the Lewinsky scandal captured on television would aid Rwanda in garnering attention to their plight and help raise much needed funds for basics such as clean water, medical supplies, and clothing.

Unfortunately, looking at the evidence surround the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, many agree with Philip Gourevitch’s conclusion that “the lesson of Rwanda is that ‘endangered people who depend on the international community for physical protection stand defenseless’” (Hentoff). Only fifty years after the horrifying events of World War II and the world’s promise to never such a disaster happen again, the debacle in Rwanda is cited as the fastest genocide in recorded history. Leading countries and world leaders avoid desperate situations needing immediate assistance, as seen through the murders in Rwanda in April 1994. Mixed information, reluctance to interfere, and selfishness over funds all contributed to the continuance of slaughter in Rwanda. The policies, actions, and words addressing the genocide point out undeniable failure in dealing with the grave situation appropriately. Stephen Pope explains in “The Politics of Apology and the Slaughter in Rwanda” the lesson everyone should learn from the Rwanda debacle:

Those with power must take responsibility to the powerless with grave moral seriousness. We should not allow our conscience to be bought off with a sporadic infusion of aid nor our national guilt to be absolved by inauthentic apologies after the fact. Choreographed prayers breakfasts, photo ops on church steps and orchestrated displays of remorse are no substitute for the courage to tell the truth about ones’ own wrongdoings.

| Top of Page |

California, United States